My Blind Date With a Troll

By Duke Harten

The maître d’ raises his eyebrow at me, suspicious-like, then says right this way. Off we go through a labyrinth of high tops and bar stools, past the lounge, around the corner—flock of waiters falls silent as we pass—into the dining room. “Here you are, miss,” he says. Poof, like magic, he’s gone.

I sit down and swallow hard, craving a drink. Already I regret not arranging for a friend to phone me with some emergency because I can see—anybody can see—that this guy is a troll.

“I’m Elroy,” he says.

“I’m Melanie,” I say.

“Let me guess: Sue skipped the part where I’m a troll.”

I cough. “Come again?”

“Oh, you mustn’t be polite. It’s the same with pirates—nobody ever asks what happened. We just pretend the eye-patch isn’t there.”

I search for words.

“Melanie,” says Elroy, flashing a smile that might be alluring if I were blind. “Relax. It’s just dinner.” He plucks a long black hair from one of his facial warts. “Let’s get you a drink.”

When the whiskey ginger arrives, I can’t help but notice it’s all whiskey and no ginger. A charitable bartender, then. I make a note to thank the man on my way out.

“So, Sue tells me you’re in finance,” says Elroy.

“I am. Investment banking.”

“You enjoy it?”

“It’s a living. Sue didn’t mention what you do.”

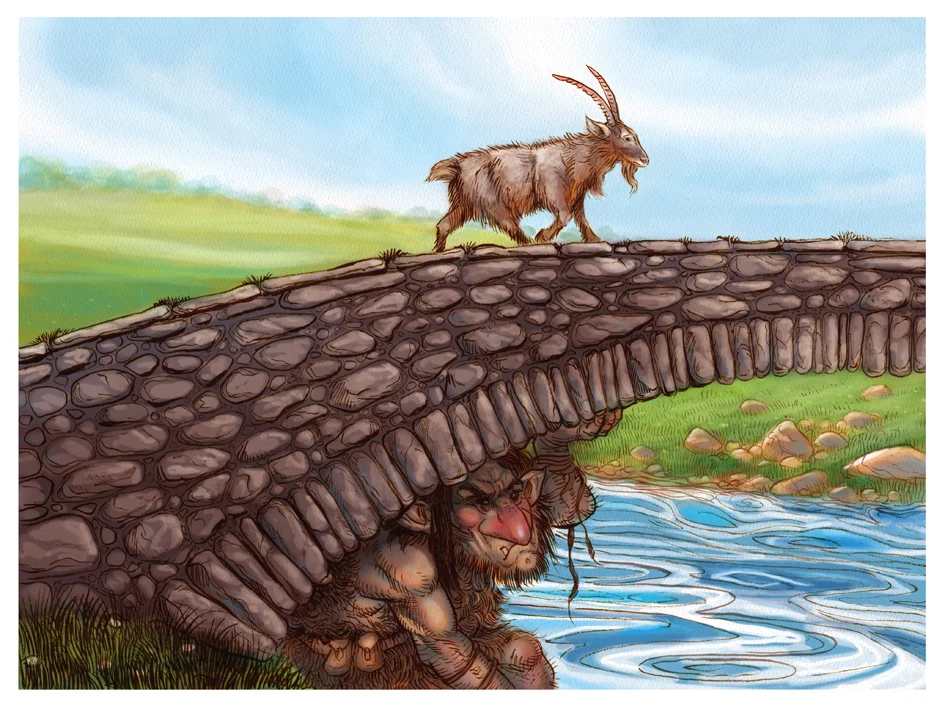

“I sit under my bridge and wait for men to fight,” he says, peering at the menu. “Oh, they have goat. Wonderful.”

“I thought you lived in caves,” I say, before I can stop myself.

“There are several types of trolls,” says Elroy, unfazed. “Bridge trolls, cave trolls…”

“What kind of men do you fight?”

“Heroes, mostly. Knights, or other kinds of heroes. A lot of knights looking to vanquish a troll.”

“Are you vanquished often?”

“Almost always,” says Elroy. He takes a sip of his wine. “A lot of people wouldn’t like it, getting vanquished for a living. But I can’t imagine the alternative: daily grind, nine to five, traffic in, traffic out.” He shakes his head. “No offense,” he says, holding up a palm to indicate that this routine works for some people—me, for instance—but just isn’t his thing.

“No, no, please,” I say. “I understand. I wanted to be an actress for the longest time.”

The confession is out before I know it’s happened. Some drink, this whiskey ginger.

“An actress,” says Elroy, raising an appraising eyebrow. A large incisor juts from his lower lip, the product of poor orthodontic therapy—he fingers the tip of it absently, thoughtfully. “Did you act in college?”

“High school,” I say.

Elroy nods. “My father was a drama teacher. He’d have liked you.”

This strikes me as a weird (but sweet?) thing to say. Before I can reply, the waiter appears. “Ah, yes, wonderful,” says Elroy, “Can you tell me: the goat—is it braised? Roasted?”

The waiter launches into a spiel about the goat. I finish my drink. Elroy asks whether they’d do a goat tartare for him—“I’m afraid I’ve developed something of a taste for it,” he says—and I tap the rim of my glass to indicate that yes, I’ll have another drink.

- - -

The next morning: sun raking eyeballs, birdsong clawing earballs, a discarded Fritos bag filled with dirt as my pillow. I roll over and watch a centipede crawl out of Elroy’s nose. His snore is palpable. I gather my clothes and take inventory: throbbing migraine, check; sensitivity to light, check; a foul dryness of the mouth—how many drinks did I have? Elroy’s sleeping mass shifts slightly and emits a trumpet of gas.

The place is, I must admit, oddly charming. If you ignore the abundance of lichen, trash, and goat bones, Elroy’s under-bridge home has got some style. My favorite touch? A boulder near his bed engraved with a scorecard: KNIGHTS, twenty-six tallies, ELROY, two.

“Rise and shine, and give God your glory,” says Elroy, sitting up and rubbing crusties from his eyes. He laughs. “A ditty my mother used to sing while we got ready for school. She would’ve liked you.” I mumble something about an early meeting. “Nonsense,” he says, waving me off. “I expect a goat will happen along soon enough, and then we can have breakfast.”

True to my lover’s prediction, a small goat comes clopping over the bridge after several minutes. “Who goes there?” bellows Elroy. The stench of his morning breath hits me like an aluminum baseball bat. My nose starts bleeding. But mingled in the rotten odor of mucus and goat tartare is something primal and aphrodisiac—like the smell of men at the gym, it encourages another sniff.

“Me, a goat,” says the goat.

Elroy hoists himself up and clambers onto the bridge. “This is my bridge, little goat,” he says. “What business have you crossing it?”

The goat bleats with fear. “The meadows back there are shot. I’m hungry and small and must needs cross this bridge to find sustenance in a meadow yonder.”

Elroy roars. “The hunger of a goat concerns me not! I will gobble you up, little goat, and use your bones to pick my teeth.”

The goat backs up some paces and shakes its head. “But listen, ye mighty troll: I have a brother, who follows not far behind. He is fatter and tastier. It would appease you little to eat a bundle of sticks such as me.” I can see this gives Elroy pause.

“Elroy,” I whisper, and beckon. He tells the goat to hold on and comes over.

“What is it?”

“I know this trick. The brother will tell you the same thing—they have an even older and bigger brother, who follows not far behind. Then once that guy gets here, he’ll knock you off the bridge with his horns.”

Elroy scratches his chin, then his ass. “How do you know this?” he says.

“Oldest trick in the book,” I say.

Elroy thinks for a moment, then nods. He scrambles back up onto the bridge. “Nice try, goat,” he says, and then tears the small animal limb from limb, using a pointed yellow fingernail to eviscerate the thing. He strips it of its skin like one might strip a pillow of its case, then bounds over to me to share the spoils. “Here you go,” he says.

“Thanks,” I say.

We eat in silence. After our bellies are full, I pull on my shoes and fix my hair. “This was really nice,” I say.

“Can I call you?” says Elroy.

I nod. “Let me give you my card.” I’m fishing in my purse when I hear the clank of metal on metal.

“Oh, Jesus,” says Elroy, rolling his eyes.

“What is it?” I say.

“What do you think?”

“Maiden!” cries a voice from above. I look up. Leaning over the bridge is a handsome knight clad in bright armor. “Your ordeal is nearly through—I will vanquish this troll and deliver thee from torment!”

“It’s okay,” I tell the knight. “I’m actually with this guy.”

The knight looks confused. “Seriously?” he says.

“Our friend Sue set us up.”

“Your friend Sue set you up with a troll?”

“I know. But it was actually really nice. We went to Auberge Michel.”

“Wow,” says the knight. “How did you get a table at Auberge Michel?”

"They had a cancellation,” says Elroy. “It was dumb luck, really.”

“That’s unreal,” says the knight. “I’ve been dying to get there. I saved a damsel last week and she was like, ‘Let’s go to Auberge Michel,’ and I was like ‘I’m a knight, honey, not a sorcerer.’”

The three of us laugh.

“Hey,” says Elroy, “We have some goat left over, if you’re hungry.”

“Really?” says the knight. “I actually haven’t eaten today. You don’t mind?”

“No,” I say, “Come on down.”

The knight removes his coif and sheathes his sword. “This is really nice of you,” he says. He descends the muddy incline and extends his hand to Elroy. “I’m Prince Deacon of Fairworth,” he says. Elroy grabs the knight by the torso and dashes his head against the bridge’s stonework until there’s nothing left except a bloody stump of a neck.

“So, I’m free next weekend,” Elroy says, chiseling another tally into the ELROY column on his boulder. “If you’re around.”